Over the countless centuries, there have been many ships that have fallen prey to accidents because of natural calamities as well as human interference in the maritime world. As we have encountered not only the loss of marine life but also human life in our previous blogs, in this one we bring you the crucial pages of history to find some of the exquisite maritime treasures that have been reclining on the ocean’s floor. The next one on our list of Major Shipwreck in the History of Maritime is MS ESTONIA which described an unprecedented disaster in the history of the maritime world.

The MS Estonia was a large cruise ferry that sailed for the former ferry company Estline’s Tallinn-Stockholm line in 1993. The cruise was built at Meyer Werft Shipyard in Papenburg, Germany, in 1980. Earlier known as Viking Sally (1980–1990), Silja Star (1990–1991), and Wasa King was eventually named MS Estonia. It was considered the second-largest cruise ferry in the world. The vessel was 155,43 m long and 24,21 m wide, with a max possible speed of 21 knots. There were 1,190 cabin beds, and two-car decks had room for 460 vehicles.

On 28 September 1994, the ship was sailing en route to Stockholm. The ship was carrying 989 people 803 passengers and 169 crew members. The weather began to turn rough in the Baltic Sea. The first sign of trouble was noticed when a loud metallic bang caused by a wave was heard. The ship began to take on a heavy list to starboard. Water flooded the car deck and the ship rolled onto her starboard side. The ship sank at about 1:50 am with the 989 people who were on the ship, only 138 survived the disaster. After the sinking, many safety regulations were introduced.

The accident was initiated by the failure of the bow visor attachments under wave impact loads. The failure was primarily due to local overload. The attachments were not designed to withstand even the rather moderate wave condition at the time of the accident. The locking devices were not manufactured properly according to the design intent. The forward ramp was integrated into the visor structure and was thus forced open when the visor attachments failed. There was no collision bulkhead extension in proper position according to SOLAS. The ramp was located to far forward to fulfill the requirements. The fully open car deck on this ferry design makes them extremely sensitive to water ingress. The officers did not reduce speed or change course when the first indications of something being wrong at the bow or the forward part of the car deck were noticed. The bow visor could not be seen from the conning position, and the indicator lamps for the locked visor did not detect the failure of the locking devices. The ship was turned towards the waves when the ship started to heel over. The rapidly developed list to starboard could not be compensated by the heeling tanks since the port tank already was full at departure. The narrow passages in accommodation areas and the staircases quickly became crowded with injured and panic-stricken people. It was almost impossible to reach open decks when the list was more than 30°. Only about 300 people reached outer decks. The lifeboat alarm was not given until about five minutes after the list developed. No information was given to passengers over the public address system. None of the lifeboats could be launched properly. It was difficult to launch life rafts and most of the rafts were water trapped or overturned at sea. Assisting vessels did not generally find it possible to rescue people from the sea.

The first helicopter arrived about 90 minutes after evacuation had become impossible. The capacity of helicopters was limited as most of them could not land or lower survivors onto the surrounding ships. Only one helicopter managed to rescue more than 15 people in total. Passengers who had escaped the ship now found themselves adrift in the stormy seas. Knowing the body temperature falls upon falling asleep, the survivors did their best to stay awake, but many fell asleep and died of hypothermia. Others began hallucinating and attacked fellow passengers, only to be knocked unconscious and die. The fierce storm was also taking it too. The waves washed survivors off their rafts and they died. For those who weren’t washed away, all they could do was to wait, hope, and pray for rescue. In total, 138 survivors were rescued, but 1 later died in the hospital. The vast majority of the survivors were young men. 7 people over 55 years old survived. 852 of the 989 passengers and crew onboard Estonia were lost.

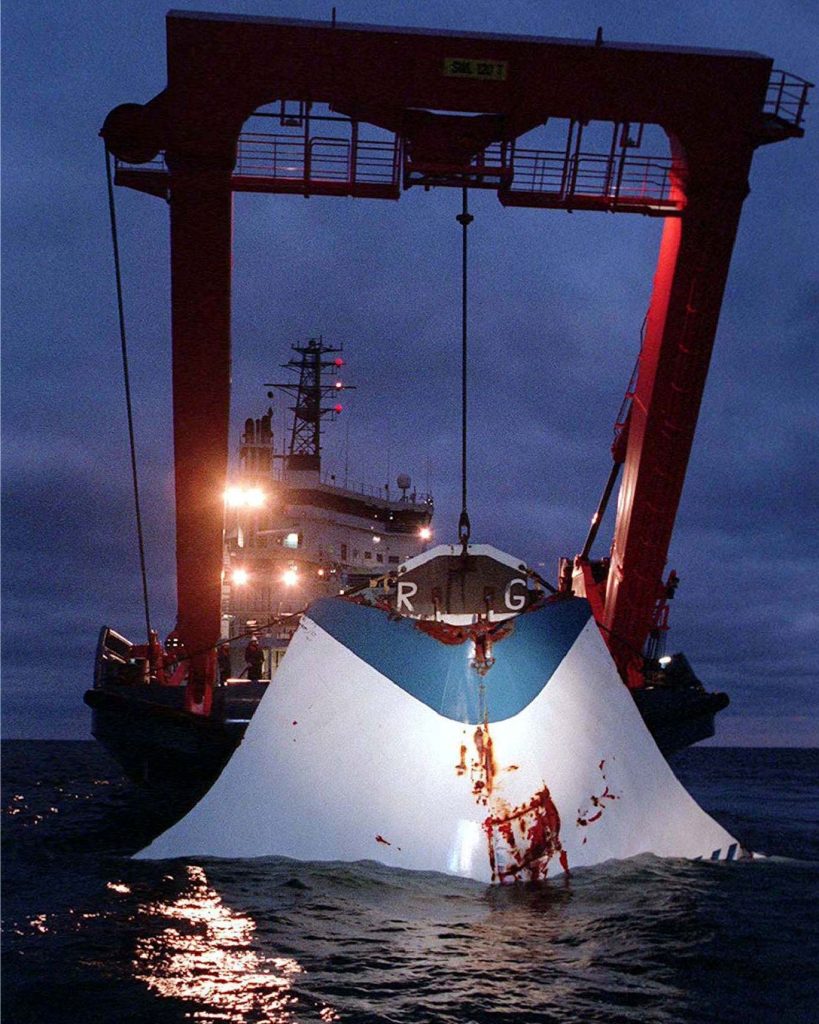

The Sinking of Estonia was met with skepticism. Estonia had been given a golden pass, declaring for the ship’s fit to sail anywhere in the world, yet the ship had sunk with a great loss of life and everyone wanted to know why. The day after the sinking, the investigations began. The inquiry, made of officials from Finland, Sweden, and Estonia interviewed survivors to find out what happened. They were surprised to see the number of surviving crew members to be far higher than what was acceptable. They also found to their surprise that there were very few female survivors and no surviving children. When the survivors were asked about the events leading up to the disaster, they reported that the ship was rolling heavily in the waves and metallic bangs from the front. This was an indication that the bow visor fell off, a theory that was confirmed when the visor was found separated from the ship.

To be continued…