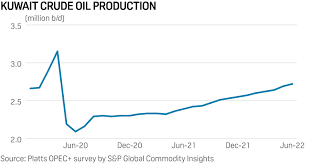

Kuwait is close to exhausting its production capacity, capping its ability to bring on more crude oil supplies to meet elevated global demand, as OPEC faces pressure from its key customers for price relief.

The country may have about 30,000 b/d of production upside left from current levels, according to Platts Analytics, with its main field aging and an unfavorable business climate, along with government instability, limiting its ability for further growth.

Kuwait pumped 2.72 million b/d in June, according to the latest Platts survey of OPEC output by S&P Global Commodity Insights.

State-owned Kuwait Petroleum Co.’s plans to raise production capacity to 4.75 million b/d by 2040 were seen as very ambitious when unveiled in 2018. The country has now revised its target to 3.5 million b/d by 2025 and 4 million b/d by 2040, but analysts say even this maybe an uphill task.

Kuwait’s main source of supply is the massive Greater Burgan field — the world’s second largest — which is already producing at up to 95% of its capacity, with its about 1.6 million b/d of output sustained through a mix of gas injection and water flooding.

KPC is working on a 100,000 b/d capacity gathering center at Burgan, and continuing development at the Neutral Zone the country shares with Saudi Arabia, which remains technically difficult after facilities there were shuttered for several years, sources say.

Beyond that, any other major additions would not come online until the end of the decade and would require international funding and expertise, which remains a challenge for famously foreign investment-averse country.

Political deadlock

Kuwait’s fractious politics are another barrier. The country currently does not have a functioning parliament, and newly appointed Prime Minister Sheikh Ahmad Nawaf al-Sabah has been tasked with forming a new government as the country awaits elections.

Current oil minister Mohammed al-Fares, who will represent Kuwait at the upcoming OPEC+ meeting Aug. 3, could go in an eventual cabinet reshuffle.

This leaves Kuwait and its oil policy somewhat in limbo.

Upgrades to its aging fields require international knowhow, which would require changes to the country’s petroleum law to incentivize oil majors to participate, analysts say.

“International companies are reluctant to come to Kuwait, if we do not do some sort of sharing or buyback agreement like they did with Abu Dhabi, Qatar [and] Oman,” independent Kuwaiti oil analyst Kamil al-Harami said. “But this is very, very hard, if not impossible, for us to observe or to comply with.”

Kuwait’s reliability as a supplier could come from its export of oil products through its investments in the downstream sector such as the 615,000 b/d Al-Zour refinery, al-Harami added. The refinery is still in the testing phase, with full capacity expected to be realized by early 2023.

Over the medium term, Kuwait is expected to see incremental production of heavy oil from the second phase of the Lower Fars development, set to come online by 2023, adding up to 200,000 b/d by the end of the decade.

Fields in the Neutral Zone are also expected to add to Kuwait’s output, though no projects have been sanctioned yet.

At any rate, much of the output is largely expected to offset declines from the Greater Burgan reservoir.

The country is also expected to develop and sell condensate volumes from its Jurassic non-associated gas projects in northern areas, such as Sabriya. The condensate is expected to be sold as crude oil under Kuwait Super Light grade.

Japanese lifeline

A possible lifeline for Kuwait could be loan facilities from buyers, which would allow their service companies to participate in upgrades and lock in a secure market share for future output.

In March, Japan’s Nippon Export and Investment Insurance signed a preliminary agreement on energy cooperation with KPC.

The MoU also has provisions for a consortium of Japanese and western banks to provide $1 billion in a loan facility to KPC to help the company boost its upstream capacity.

However, the resignation of the Kuwaiti government in April and the dissolution of the parliament for the second time this year in July have delayed plans.

One Japanese banking source said the loan facility was a “work in progress.”

Japan has been looking to diversify its crude imports from Russian oil following Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine in March, and Kuwait was its third-largest supplier in 2021.

Japan also has a historical reason to be invested in Kuwait’s upstream sector after it lost the concession to the Khajfi oil field in the Neutral Zone through its Arabian Oil Co. when it expired in 2003.

“Many Japanese involved in these negotiations felt bitter about it,” a source with knowledge of the past discussions said.

The loan facility could help Japan reenter Kuwait’s upstream sector, revive output and help the country’s crude exports.

“Kuwaiti oil seems fitting in a sweet spot of medium sour for Japan, so in essence, yes, so it’s safe to say the crude is quite valuable,” the source said.

Source: Hellenic Shipping News