Mumbai: Two Nobel laureates — one decoding the chemistry of life, the other the economics of nations — came together in Mumbai on Wednesday to reflect on how science, politics, and technology are shaping humanity’s future.

David MacMillan, recipient of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for pioneering asymmetric organocatalysis, and James A. Robinson, the 2024 Economics laureate celebrated for his research on institutions and prosperity, spoke at the Nobel Prize Dialogue India 2025, organised by Tata Trusts.

Their wide-ranging discussion spanned the promise and limits of artificial intelligence, the paradox of China’s rise, and the global inequality that continues to divide societies.

China’s paradox of control and creativity

Robinson said the success of China’s state-driven prosperity poses a challenge to traditional liberal economic models.

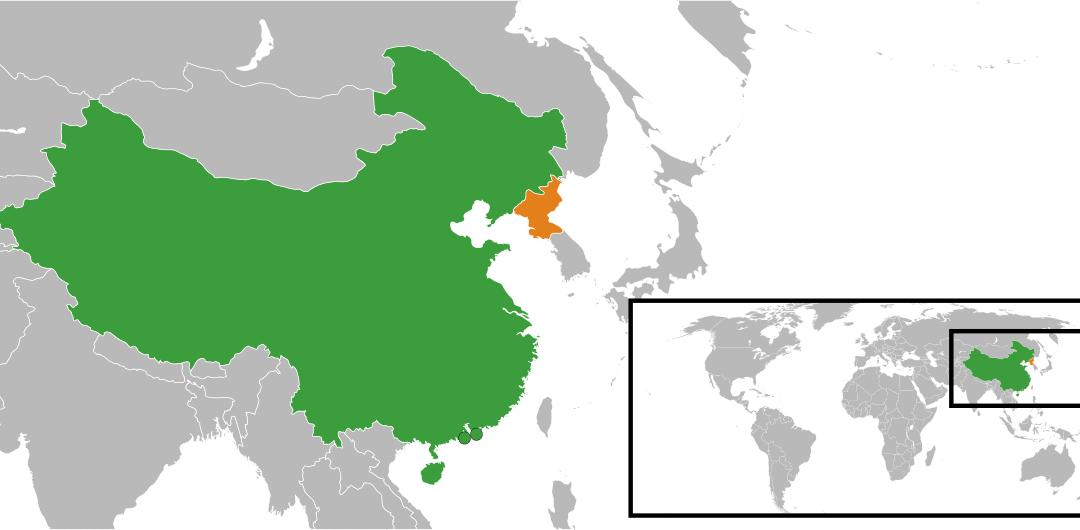

“The Chinese people are incredibly innovative and driven. That energy fuels the country’s economic dynamism,” he said. “But the Communist Party’s urge to control and maintain power cannot coexist indefinitely with the creativity that drives innovation. Something has to give.”

Drawing historical parallels, he added: “In Korea and Taiwan, the political systems eventually opened up. In China, I don’t see that happening. The leadership appears willing to sacrifice everything to stay in power. North Korea is a better model of what China could look like in the future.”

The Nobel question: Why not India?

Asked about why some countries haven’t produced Nobel winners in science for decades, Robinson said that the concentration of resources in rich nations gives them an advantage.

“Basic research thrives where there are strong institutions, resources, and education systems. That’s why talent from across the world gravitates to countries like the United States,” he noted.

MacMillan, however, cautioned against seeing Nobel recognition as the goal.

“The goal should be to do something meaningful that ends up deserving a Nobel Prize — not to chase the prize itself,” he said. “India has made impressive strides in research. I visited the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and saw outstanding young scientists doing world-class work. India is more primed than ever to make global breakthroughs.”

AI: A tool, not an inventor

Both laureates agreed that artificial intelligence has immense utility but clear limits.

MacMillan observed that in chemistry, AI can optimise reactions and processes but still lacks the creativity to invent new ones.

“It’s great for improving what already exists, but it can’t imagine what doesn’t,” he explained. “AI might identify promising molecular combinations, but it’s the chemist who must actually bring them to life.”

Robinson echoed that sentiment in the context of social science.

“I use AI to process questions that were once impossible because of computational limits,” he said. “But it doesn’t generate new ideas. It’s a tool that amplifies what we can do, not something that replaces the human element.”

Balancing innovation and inequality

While AI’s benefits in research are clear, Robinson warned of its broader economic consequences.

“In the real economy, AI risks replacing people, lowering wages, and deepening inequality,” he said. “That’s where the downside lies.”

The discussion closed on a shared note of optimism: that science, creativity, and democratic openness — when allowed to flourish — remain humanity’s best chance to shape “the tomorrow we want.”