After decades of strict population control, China is now grappling with the opposite crisis: too few births. The country that once enforced a one-child policy is now experimenting with unusual ideas to encourage families to have more children — from taxing condoms to proposing dating courses in schools.

The urgency is driven by stark new data. Government figures released this week show China recorded its lowest birth rate since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. The population fell for the fourth consecutive year in 2025, declining to 1.404 billion — about three million fewer people than the year before, according to data cited by the Associated Press.

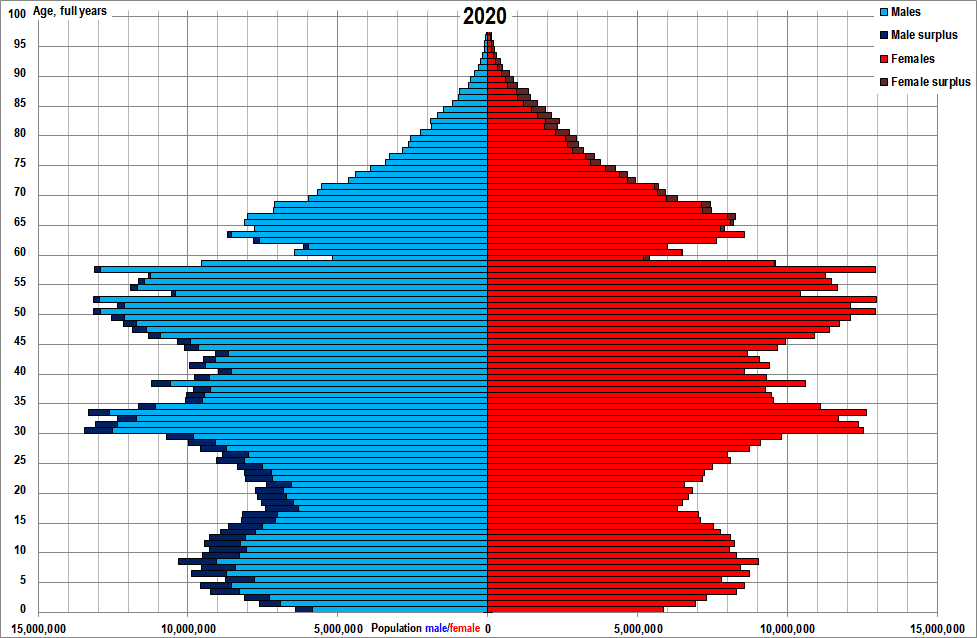

The implications are profound: the workforce is shrinking, the population is ageing rapidly, and the economic model Beijing built over decades is under strain.

What the latest numbers show

China’s birth rate fell to 5.63 per 1,000 people in 2025, with 7.92 million babies born — a 17% drop compared with 2024.

While 2024 had seen a brief uptick in births, the rebound proved short-lived. China last published an official fertility rate of 1.3 in 2020, but independent estimates now place it closer to 1.0, far below the 2.1 needed to maintain population stability.

For comparison:

- South Korea: ~0.7

- Japan: ~1.26

- United States: ~1.6

The result is a demographic imbalance: fewer young people supporting a growing elderly population.

From limiting births to desperately promoting them

For much of its modern history, China saw population as power. In 1957, Mao Zedong famously declared that China’s 600 million people were its greatest strength.

That view shifted in the late 1970s after years of famine and economic strain. In 1980, Beijing introduced the one-child policy, limiting most urban couples to a single child. The policy remained in force for more than 35 years and reshaped society in lasting ways:

- A gender imbalance driven by son preference

- Generations of only children

- Rapid population ageing

- A shrinking urban workforce

The policy was relaxed to allow two children in 2015 and three in 2021 — but by then, social habits had already changed.

Why Chinese families aren’t having more children

Ending the one-child policy did not trigger a baby boom. Instead, it collided with modern realities.

- Economic pressure

Raising a child in urban China is expensive. Housing, education, healthcare and tutoring costs have soared. With slowing growth and high youth unemployment, many couples say they simply cannot afford more children.

- Changing social norms

Marriage rates are falling. Many young people, especially women, are delaying or rejecting marriage and parenthood altogether. Long work hours and intense competition leave little room for family life.

- Lingering effects of past policy

People raised as only children often internalised small-family norms. Parenting also shifted toward heavy investment in a single child — sometimes described as the “little emperor” phenomenon.

- Cultural timing

Birth rates in 2025 were further dampened by the Year of the Snake, which some consider inauspicious for childbirth under the Chinese zodiac.

Beijing’s response: Subsidies, tax tweaks and social engineering

With persuasion replacing coercion, the government has rolled out a mix of financial incentives and social messaging:

- Cash subsidies: Up to 3,600 yuan ($500) per child in some regions

- Tax changes: Condoms now taxed at 13% after losing VAT exemption

- Tax breaks: For kindergartens, daycare centres and even matchmaking services

- Propaganda campaigns: Promoting “positive attitudes” toward marriage and childbirth

- Five-year plan goals: Reducing child-rearing costs and expanding family support

But experts say these measures barely offset the real financial burden of raising children — and they fail to address deeper structural problems.

The economic risk: Growing old before growing rich

China’s population is ageing at extraordinary speed. The country now has 323 million people over the age of 60 — about 23% of the population, and rising.

This creates three major risks:

- Slower economic growth

China reported 5% growth in 2025, but analysts expect that to decline as the labour force contracts and productivity gains taper.

- Pension and healthcare strain

More retirees mean heavier pressure on pensions and healthcare systems. Economists warn China will need major reforms to sustain public spending.

- Industrial transition challenges

Beijing wants to shift from labour-intensive manufacturing to high-tech industry. But automation cannot fully replace human workers — especially in a consumer-driven economy.

Scholars summarise the dilemma bluntly: China is “getting old before it gets rich.”

Global implications: Population as power

Demographics have long shaped China’s geopolitical identity. Under President Xi Jinping, population size is framed as national strength — a “great wall of steel forged by 1.4 billion people.”

That narrative has gained new relevance since India overtook China as the world’s most populous country in 2023. Demographic size influences markets, diplomacy, influence in the Global South, and long-term strategic power.

What happens next?

China now faces a demographic challenge with no easy solution. Japan and South Korea offer cautionary examples: once fertility rates fall too far, they rarely recover.

Beijing’s success may depend on whether it can:

- Make family life affordable

- Reform pensions and welfare

- Reduce pressure on working parents

- Encourage stable relationships

- Sustain economic confidence

For a government that once worked relentlessly to limit births, the new challenge is deeply ironic — and far harder:

How do you persuade a society shaped by decades of restriction that it should now choose to have more children?