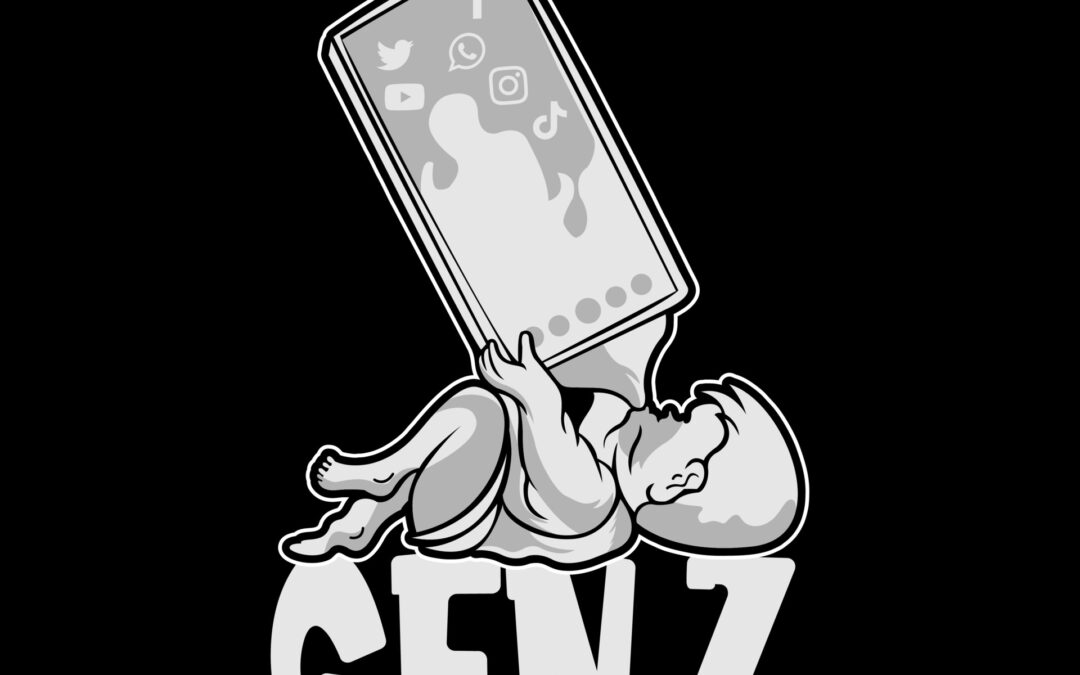

DEHRADUN: In Uttarakhand’s hill villages—long marked by outmigration and dwindling populations—a quiet political transformation is underway. A new generation of Gen Z pradhans, many of them women and barely out of college, is stepping into local governance with smartphones in hand and degrees behind them. Their goal is clear: to rebuild the villages they call home.

When the latest panchayat election results were declared in late July, a wave of young women emerged as first-time village heads, replacing leadership long dominated by older generations. Just months into their tenure, they are already challenging two entrenched realities of the Himalayas—migration and patriarchy. In doing so, they are also dismantling the familiar “pradhan-pati” model, where husbands wield power behind the scenes. For these 20-somethings, the panchayat is not a path to status or wealth, but a deliberate decision to return home and invest in their communities.

Their ambitions are expansive: improving schools and healthcare, fixing roads, and most importantly, slowing the steady exodus of young people leaving the state in search of opportunity.

At 22, Sakshi Rawat could have taken up a laboratory job in Dehradun. Instead, just three months after completing her biotechnology degree, she returned to her village, Kui, in Pauri Garhwal, to serve as pradhan. While her peers pursued private-sector jobs in cities, Sakshi chose a different route. “Most youngsters leave their villages after studying,” she said. “I want them to stay and build something of their own here.”

Inspired by young grassroots changemakers like Pawan Bisht of nearby Maroda village, Sakshi believes Uttarakhand’s revival must be led by its youth. “The biggest challenge isn’t geography or funding—it’s mindset. People still think success lies outside the village. Real change will happen when people see results at home,” she said.

In Sarkot village of Chamoli district, 21-year-old Priyanka Negi once dreamed of becoming a mathematician. Her father, a two-time village head, noticed her interest early and began taking her to block-level meetings. “I always loved numbers,” she said, “but during my graduation, I realised governance is the real math.” Her focus is straightforward: better road connectivity. “Fix the roads, and half the problems of hill life get solved,” she said.

For 22-year-old Deeksha Mandoli, leadership arrived early, alongside major life responsibilities. Married at 20 and a mother by 21, she is now the pradhan of Gulari village in Chamoli. An English graduate, Deeksha sees youth addiction as a growing concern and calmly rejects the old “pradhan-pati” stereotype. “People now come to us directly,” she said.

In Chari village, also in Chamoli, Kiran Negi—pradhan of a village with just 250 voters—is the youngest from her block to take charge. “The village may be small, but the problems aren’t,” she said, pointing to issues like roads and water supply. The absence of a male figure by her side, Kiran noted, has made her leadership more visible and decisive—challenging the notion that ambition and progress belong only to cities.

Together, these Gen Z pradhans are reshaping grassroots politics in Uttarakhand, proving that digital fluency, determination, and a sense of purpose can redefine rural leadership—and perhaps even reverse the tide of migration.